The author(s) will give a talk

Human paleo-genomics and Beringian landscapes

1 INSTAAR

2 University of Kansas

3 University of Kansas

4 University of Kansas

5 The Mammoth Site

6 INSTAAR

7 University of California-Berkeley

8University of Nevada-Reno

Paleo-genomics has fundamentally altered the study of the human past, including the global dispersal of modern humans and the peopling of Eurasia, Australia, and the Western Hemisphere. This is due in large measure to methodological advances, such as high-throughput sequencing, which moved the field beyond the mtDNA and Y-DNA studies of the 1990s to whole-genome analyses, as well as successful extraction of ancient DNA (aDNA) from dated human remains throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere (i.e., where conditions permit long-term preservation of DNA).

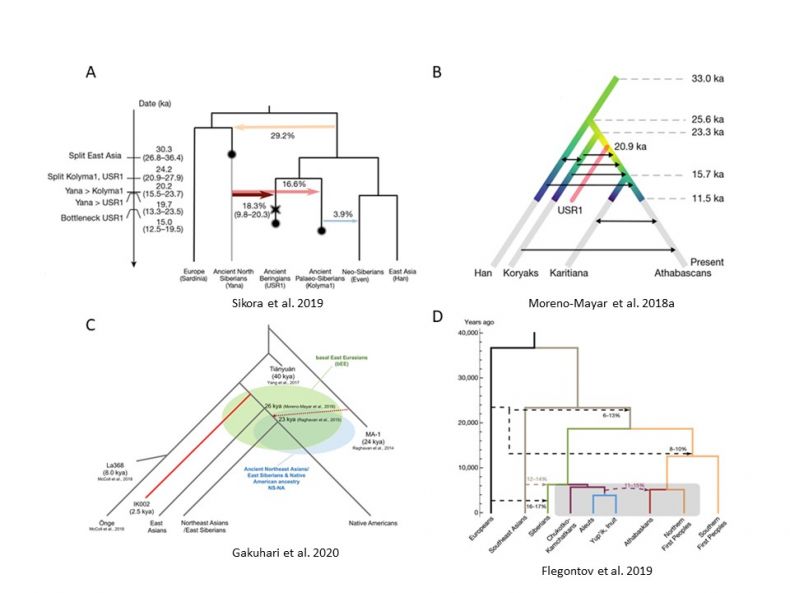

In Northeast Asia and Beringia, aDNA analyses of human remains excavated in earlier decades have been supplemented with analyses of spectacular recent finds in Siberia and Alaska (e.g., Raghavan et al. 2014; Tackney et al. 2015; Sikora et al. 2019), where a number of ancient lineages now have been identified. Among these lineages are several that contributed significantly to the genome of the First Peoples of the Western Hemisphere and have potential to shed light on the process by which it was settled—and the role of Beringia in this process (see Figure 1).

Siberia was alternately settled by people derived from western Eurasia (beginning with the initial dispersal of modern humans >45 ka) and East Asia (i.e., from the south). Beringia, in turn, was alternately settled by people in Siberia derived from western Eurasia and mainland East Asia. It was initially occupied by a west Eurasian lineage (labelled Ancient North Siberians) before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), but, by the end of the LGM, both Siberia and Beringia were occupied by peoples who were primarily descended from an East Asian lineage (e.g., Sikora et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2020).

Both the west Eurasian and East Asian groups appear to have arrived in Beringia via the “Great Arctic Plain” (exposed East Siberian Arctic Shelf) rather than the Northeast Asian maritime zone (i.e., North Pacific coast). The former was largely exposed during later MIS 3 and supported a diverse steppe-tundra large mammal community before and during the LGM (e.g., Schirrmeister et al. 2005; Sher et al. 2005; Pitulko et al. 2017). South of the Great Arctic Plain, access to Beringia from Siberia was mostly blocked by local glaciation, including the Verkhoyansk Mountains, during the LGM (Batchelor et al. 2019).

By the end of the LGM, the ancestral First Peoples were present in Beringia (they dispersed widely in the Western Hemisphere during 15–13 ka). Analysis of aDNA from dated human remains indicates that at least two other lineages (labelled Ancient Paleo-Siberians [APS] and Ancient Beringians [AB]) were present in Beringia by the early Holocene. All three lineages are descended from an East Asian population, although two (APS and AB) received gene flow from a west Eurasian group. The APS and AB lineages diverged ~24 ka, and the First Peoples diverged from the AB population ~20 ka (Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018a, 2018b; Flegontov et al. 2019; Sikora et al. 2019).

If there is broad agreement among the paleo-genomic models with respect to the lineages and their relationships, there is a debate about where the divergence of the APS and AB lineages took place, and where the ancestral First Peoples split from the latter. Some researchers (e.g., Sikora et al. 2019) concluded that these groups were located in Beringia during the LGM, while others (e.g., Yu et al. 2020) argued that none of these lineages occupied Beringia until after the LGM.

The debate is central to the larger question of the role of Beringia in the peopling of the Western Hemisphere. Currently, there are no human remains in Beringia dating to the LGM (27–15 ka) and although there is some evidence for humans in Beringia during this interval (e.g., Vachula et al. 2020), it is widely regarded as problematic.

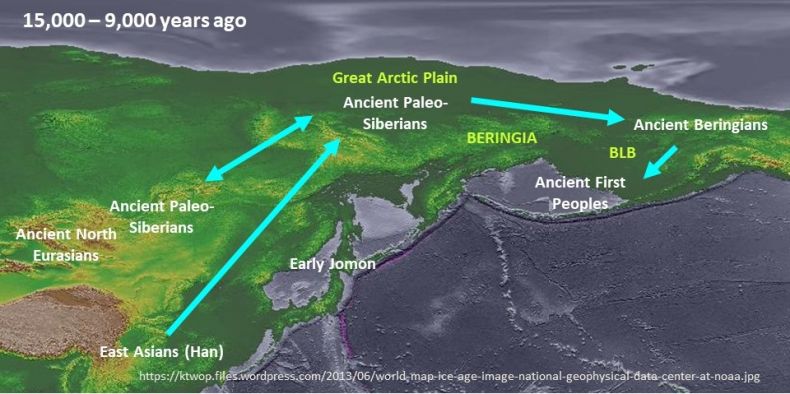

Here, we address the question of Beringia’s role in the peopling of the Western Hemisphere by mapping lineages identified in the paleo-genomic models for the post-LGM and early Holocene (15–9 ka) on an LGM landscape (see Figure 2). It is a heuristic exercise, designed to illustrate the spatial or geographic aspect of the problem of where the First Peoples and closely related lineages (especially APS and AB) were located during the LGM and, more generally, to help integrate the paleo-genomics with the environmental setting.

The map reflects the effects of lower sea level on coastlines (glaciation is not shown). Northern Japan is joined to Sakhalin and the Russian Far East (“Paleo-Sakhalin-Hokkaido-Peninsula”), while the exposed East Siberian Arctic Shelf represented an immense plain (“Great Arctic Plain”) adjoining the modern arctic coast of Siberia mentioned earlier. During the LGM, the southern Bering Land Bridge (BLB) expanded significantly in response to sea levels 60–70 meters below their late MIS 3 levels (Lambeck et al. 2002).

The post-LGM location of the Ancient First Peoples shown in Figure 2 is not based on dated human remains, but rather is deduced from the glacial chronology and dated remains in other parts of the Western Hemisphere. The lack of an available interior migration route between Beringia and mid-latitude North America until after 13 ka (e.g., Heintzman et al. 2016) indicates that this population was located on the unglaciated southern coast of the BLB no later than 15 ka (in order to account for the initial dispersal via the Pacific coast of First Peoples in North and South America during 15–13 ka). The AB lineage is represented by human remains from Trail Creek Caves, Seward Peninsula (~9.0 ka) and the Tanana Valley (USR1 [~11.4 ka]) (Moreno-Mayar 2018a, 2018b).

The APS lineage is represented by specimen (Kolyma1) from the Kolyma Basin (~9.8 ka). A closely related individual (UKY [~13.9 ka]) is reported from the Lake Baikal area (Yu et al. 2020). It is unclear if UKY represents APS people who moved from the Great Arctic Plain into southern Siberia after the LGM or reflects an earlier APS presence in southern Siberia that preceded their movement into Beringia. It also is unclear if the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineage, which is represented by human remains in southern Siberia dating to the LGM (~24 ka [MA1] & ~17 ka [AG3]), co-existed with APS after the LGM (Raghavan et al. 2014; Moreno-Mayar 2018a, 2018b; Sikora et al. 2019).

We offer the following observations with reference to Figure 2:

First, the map underscores the relationship between East Asians and the lineages in Beringia ~15–9 ka, including ancestral Native Americans. Although the ANE population, associated with mid/late Upper Paleolithic industries in southern Siberia, contributed to the genomes of the APS and AB groups—and indirectly to the Native American genome—the latter three are descended primarily from the direct ancestors of the modern Han population (Sikora et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2020). The latter also are the parent lineage for other modern Siberian peoples (e.g., Evenki) (e.g., Flegontov et al. 2019).

At the same time, Figure 2 illustrates the arctic route followed by the people who settled in Beringia by the end of the LGM. Regardless of when these peoples first occupied Beringia—and where they came from—they probably arrived via the “Great Arctic Plain” (i.e., exposed East Siberian Arctic Shelf). An arctic route is supported by the lack of a genetic connection between the people who occupied the Northeast Asian maritime region (Early Jomon) and the three lineages (e.g., Gakuhari et al. 2020).

During the LGM, especially after 23 ka (when a brief warm interval [GI 2] was followed by somewhat milder temperatures [22–15 ka]), the Great Arctic Plain probably offered a refugium for human groups (see above). An additional clue may be provided by the EDAR V370A allele, which underwent strong positive selection during the LGM in a population ancestral to both living Asians and Native Americans (e.g., APS). Hlusko et al. (2018) suggested that EDAR V370A represented a high-latitude adaptation to low UV radiation, which is consistent with occupation of the Great Arctic Plain during the LGM (and also with the early Holocene location of APS).

Figure 2 also illustrates the principal weakness of the hypothesis that the ANE, APS, AB, and Ancient First Peoples all were located in southern Siberia during the later LGM. How likely is it that all four populations—one of which was genetically isolated from the others—occupied the same region at this time? The problem is compounded by archaeological evidence for a significant contraction of the human population in the region during the LGM (e.g., Buvit et al. 2015).

As Figure 2 shows, the post-LGM geographic distribution of lineages in Beringia corresponds to three major regions: Great Arctic Plain (APS), eastern Beringia (AB), and the southern BLB (Ancient First Peoples) (e.g., Guthrie 2001; Crocker and Elias 2008; Rae et al. 2020). The pattern suggests that environmental variation played a role in the differentiation of the three populations.

Fig 1.

Human paleo-genomic models for Northeast Asia and Beringia for the last 40,000 years, based in part on the analysis of aDNA from dated human remains.

Fig 2.

Geographic locations of lineages after the LGM (15–9 kcal BP) imposed on a map of LGM coastlines. The three lineages in Beringia during this period are descended primarily from a mainland East Asian population (blue arrows). The western boundary of Beringia is defined here as the Verkhoyansk Mountains.